Influences, sustainability, and the essence of Design from the perspective of Architect Alessio Patalocco

Throughout your career, you’ve had the opportunity to work on projects in both Europe and Asia, particularly in China and Hong Kong. How has exposure to different cultural contexts influenced your architectural style and design philosophy? Are there specific elements that you’ve incorporated into your subsequent projects?

The experiences in China and Hong Kong have undoubtedly strengthened certain aspects of my architectural language, emphasizing the free and creative dimension of projects. Specifically, the Shinto tradition, known in Japan, has helped me understand how to work with natural and reversible elements, appreciate essential life, and realize that behind a beautiful sheet of natural wood, there is a world that tells its own story without adding anything. Above all, I’ve learned to remove elements and work more crisply and decisively on project ideas. It was only after these work experiences that the essential truly became visible to my eyes.

With the growing awareness of sustainability, how do you see the role of architecture and urban design in contributing to more ecological and livable cities? What trends do you anticipate will shape the future of urban planning?

Currently, I don’t have a very positive view of the future; I see a lot of “greenwashing” and little essence from many companies in the construction industry and beyond. I believe that if we take the Shinto tradition as a guiding principle, things would improve: cities must be designed to be regenerated and replaceable; fauna and flora should be considered as much as humans, and ultimately, we must accept that “being in nature” also means coexisting with inconvenient things, such as the smell of manure in the morning.

In 2011, you delivered a prestigious lecture during the World Congress of Architecture at the Tokyo International Forum. The slogan was “Less (Money) is More (Beauty),” a synthesis of an approach representative of your work. How do you balance financial optimization and the pursuit of aesthetic beauty in the design process? Could you share an example from one of your projects where this philosophy was particularly evident?

The economy of interventions has always been crucial throughout the history of art and architecture. For example, the seventeenth-century trompe l’oeil by Andrea Pozzo was a relatively economical system for improving the perception of certain architectures without spending resources on real architectural variants or elements. In the case of my mural painting projects, I redeveloped the perception of some residual areas with minimal expenditure by extensively using a “shock” color like magenta-pink. At the Tokyo International Forum, they greatly appreciated the use of this color. In Tokyo, I also presented the project for Piazza dell’Olmo, the first sponsorship project I carried through to its realization in 2014. In that case, companies were involved that could sponsor services or materials, reducing the total cost of the intervention—a practice I’ve repeated in other construction sites.

Beyond the need to respect client requests and guidelines, what is architecture to you, how did you decide it would be your path, and what types of work are closest to your heart?

I’ve always wanted to be an inventor and an artist, so I chose this path without hesitation. I had just a few moments of indecision between studying object design or architecture, but in reality, I knew what I wanted to do all along. Architecture, for me, is a way of making art by expressing my worldview to be applied to the reality we are modifying. The work I cherish the most is a new installation I’m working on, titled “Voyage à Calais.” It’s a kind of origami made from steel sheets sprayed on one side and left to rust on the other. It speaks about migrants and was supposed to be installed on the Calais pier in France; the artwork is commissioned by Amnesty International. Today, after various political rejections, it has found a place in the Sila forest: its final installation is scheduled for the end of February.

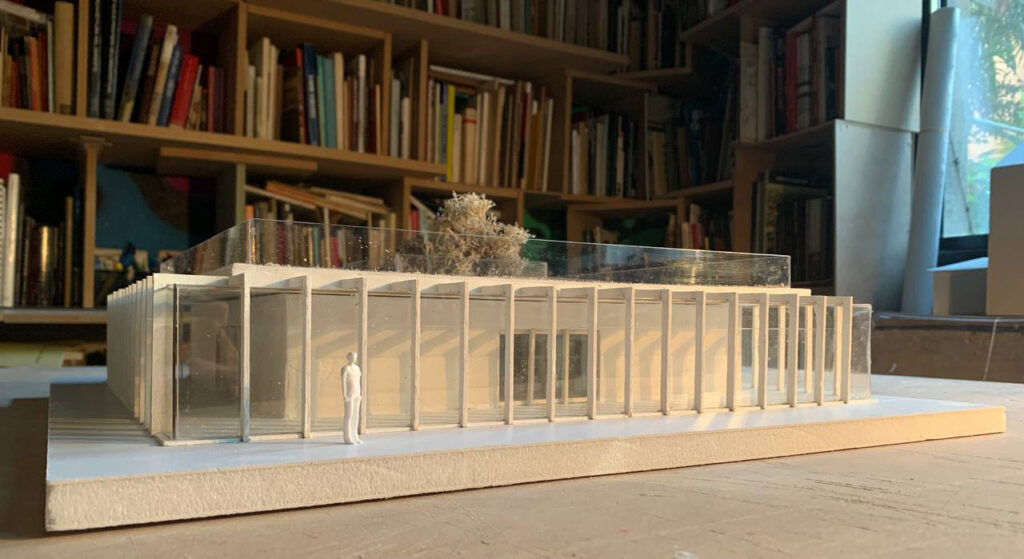

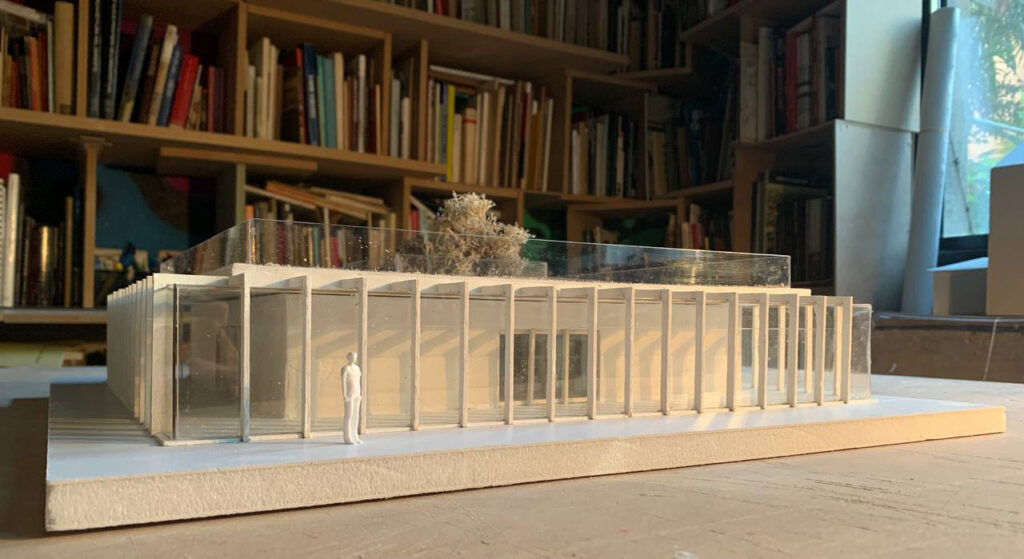

1.Permanent museum setup for an archaeological and

medieval museum in Narni (2022)

- Project for a sustainable and highly accessible and inclusive

house (2023) - Pinklandscapes project (2008-2016)

- Interior for a young couple (2021)